Austro-Hungarian Bank

The Austro-Hungarian Bank (German: Oesterreichisch-ungarische Bank, Hungarian: Osztrák–Magyar Bank, Czech: Rakousko-uherská banka, Polish: Bank Austriacko-Węgierski, Serbo-Croatian: Austro-Ugarska banka, Italian: Banca austro-ungarica, Ukrainian: Австро-Угорський банк) was the central bank of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The institution was founded in 1816 as the privilegirte oesterreichische National-Bank (lit. 'Privileged Austrian National Bank'), and changed its name in 1878 as a delayed consequence of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. It was liquidated in the financial turmoil following the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy in late 1918, and was principally succeeded by the Oesterreichische Nationalbank in Vienna, the Hungarian National Bank in Budapest, the National Bank of Czechoslovakia in Prague, and the National Bank of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in Belgrade.

Background

[edit]The first note-issuing institution in the Habsburg Monarchy was the Municipal Bank of Vienna or Wiener Stadtbank, established in 1706.[1] It started issuing banknotes in 1762, which were known as "Bancozettel". During the Napoleonic Wars, the imperial Austrian government issued paper money of its own and rapidly increased its supply to finance the war effort, causing inflation.

Austrian Empire

[edit]

After peace was restored by the Congress of Vienna, and on advice from statesman Johann Philipp Stadion, Emperor Francis I established the privilegirte oesterreichische National-Bank by imperial patent on 1 June 1816. Its shareholders were private individuals, in contrast to the municipality-owned Wiener Stadtbank.[2]: 73 Its first task was the redemption of the depreciated wartime paper money to re-establish trust in the currency.[3] On 15 July 1817, it was granted another imperial patent to issue money by printing banknotes, and had its first permanent staff by January 1818. It soon started developing its network of branches throughout the Austrian Empire.[4]

On 2 October 1841, Emperor Ferdinand I renewed the Bank's issuance monopoly, and on that occasion altered its governance to increase government control.[4] The Bank opened its first branch in Prague in 1847, and its second in Pest in 1851.[5] The Bank's notes suffered depreciation during the successive episodes of financial stress associated with the revolutions of 1848–1849, the Autumn Crisis of 1850 with Prussia, and the Crimean War mobilization from 1853 to 1856. On 27 December 1862, Emperor Franz Joseph I again renewed the Bank's issuance privilege, granted it greater independence, and emulated the UK Bank Charter Act 1844 by limiting the volume of banknotes in circulation to 200 million gulden backed with precious metal. In 1866, however, the Austrian government breached these arrangements to finance the Austro-Prussian War, and had to subsequently pay compensation to the Bank.[4]

Austro-Hungarian Empire

[edit]The matter of the central bank and its governance was set aside during the negotiations that led to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, with the understanding that it would be reformed in the future. Meanwhile, the law of 18 March 1872, based on the experience of 1866, stipulated that any money issues in excess of the 200 million-gulden limit must be backed by precious metal reserves. Backed by these provisions, the Bank managed to preserve monetary stability during the Austrian financial boom-and-bust episode of 1873.[4] By 1875, it had 24 branches outside of Vienna.[5]

The adaptation of the bank's to the Monarchy's new political structure was only finalized in 1878, when its name was changed to Austro-Hungarian Bank. The bank was given a unitary governance with a general meeting (German: Generalversammlung) and governing council (German: Generalrat) chaired by a Governor, but a dual operating structure with two separate executive teams (German: Direktionen) and head offices (German: Hauptanstalten) in Vienna and Budapest.[6] The governor was to be jointly nominated by the respective ministers of finance of Austria and Hungary, and the bank was statutorily committed to opening new branches on an equitable basis in both parts of the Habsburg Monarchy. Hungarian nationalists were not satisfied by these arrangements and kept advocating for a separate Hungarian central bank, but their efforts remained unsuccessful until the end of the joint monarchy.[7]

An 8-year transition from bimetallism to the gold standard, replacing the Austro-Hungarian gulden with the Austro-Hungarian krone, was completed in 1900. Another renewal of the bank's issuance privilege, on 21 September 1899, curtailed its prior independence. Even so, the Austro-Hungarian currency's gold parity was successfully maintained until 1914. During World War I, however, the Bank was unable to preserve monetary stability against the pressures of military expenses and economic shortages. The money supply increased thirteenfold, and prices rose sixteenfold compared to their prewar level. By late 1918, the real income of workers had been reduced to one fifth of what it had been in the last year of peace. About forty percent of the cost of war was covered by the central bank's monetary financing, and about sixty percent by war loans.[6]

Dissolution

[edit]

On 18 October 1918, the Diet of Hungary voted to terminate the kingdom's union with Austria, and on 31 October 1918, newly appointed Prime Minister of Hungary Mihály Károlyi repudiated the Compromise of 1867. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, signed on 10 September 1919, provided for the Bank's liquidation and the allocation of its assets and liabilities to successor states, namely Austria and Hungary but also Czechoslovakia, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia.

In Vienna, the Bank increasingly had recourse to monetary financing, and covered about 75 percent of the budget deficit of the new Republican Austrian state between 1918 and 1922. The Austrian currency depreciated sharply, from 16 to 30 kronen against the U.S. dollar during the first half of 1919 - and 5,275 kronen to the dollar by the end of 1921. The hyperinflation was only stopped by the protocol for the reconstruction of Austria, signed in Geneva on 4 October 1922 and entailing a harsh fiscal and economic adjustment program supported by a loan guaranteed by the League of Nations. The Bank's last ordinary general meeting was held on 14 July 1921, and the last meeting of its governing council on 15 December 1922.[6]

Governors

[edit]

- Ádám Nemes von Hídvég (17 June 1816 – 15 November 1817)

- Joseph Carl von Dietrichstein (15 November 1817 – 17 September 1825)

- Melchior von Steiner (acting, 1825 – 1830)

- Adrian Nicolaus von Barbier (4 September 1830 – 27 March 1837)

- Carl Joseph Alois von Lederer (27 March 1837 – 31 October 1847; acting, 9 February 1848 – 18 May 1848)

- Franz Xaver Breyer von Breynau (31 October 1847 – early 1848)

- Josef Mayer von Gravenegg (18 May 1848 – 9 January 1849)

- Joseph von Pipitz (6 August 1849 – 8 November 1877)

- Alois Moser (28 September 1878 – 6 March 1892)

- Gyula Kautz (6 March 1892 – 19 February 1900)

- Leon Biliński (19 February 1900 – 15 February 1909)

- Sándor Popovics (15 April 1909 – 8 February 1918)

- Ignaz Gruber von Menninger (6 March 1919 – 18 March 1919)

- Alexander Spitzmüller (19 December 1919 – December 1922)[8]

Buildings

[edit]Vienna

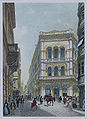

[edit]At its creation, the Bank was temporarily settled at Singerstrasse 1 next to St. Stephen's Cathedral. In 1819–1821, it purchased houses on Vienna's prestigious Herrengasse, and replaced them after demolition with a building designed by Rafael von Riegel after designs by Charles de Moreau and Paul Wilhelm Eduard Sprenger. The new building was inaugurated by Francis I on 1 July 1821 and completed in 1823.[9] Its pediment was adorned with sculptures by Josef Klieber, which were however removed when the building was repurposed in 1874.[10]: 17

In 1860, the Bank moved across the street to a new building complex designed in 1855 by architect Heinrich Ferstel, himself the son of a Nationalbank official,[10]: 18 with ornate decoration including twelve statues by Hans Gasser representing the lands of the Austrian Empire.[11] The lavish interior decoration included works by painters Franz Josef Dobiaschofsky and Carl Joseph Geiger, and sculpture by Joseph Gasser von Valhorn and Franz Melnitzky.[10]: 18 The complex also hosted the Wiener Börse (which only stayed there until 1869), a commercial mall (German: Basarhof), and from its opening in 1876, the famed Café Central.[4] In 1897, the Bank expanded into the adjacent Palais Hardegg on Freyung 1, where the Bank relocated its Austrian general management and the Governor's office.[12] In 1924, in advance of its planned relocation, the Bank sold the entire complex to the Anglo-Austrian Bank, which redeveloped it for commercial use. The complex was comprehensively renovated in 1975–1982 and has been known since then as Palais Ferstel, including the recreation of the Café Central within the complex, albeit on a different location from the original.[11]

In 1910, the Bank held a design competition for the design of a new head office in Vienna's Alsergrund district, which was won by Leopold Bauer, a disciple of celebrated Austrian architect Otto Wagner. Bauer's concept entailed a gigantic complex dominated by a massive 88-meter-high tower, partly on the location of the old Vienna General Hospital (later Campus Hof 1 of the University of Vienna). The construction of a first building intended for money printing facilities started in 1913 after demolition of the Alser Kaserne barracks, but was disrupted by World War I and stopped in 1917; the rest of Bauer's grandiose development plan was never implemented. After the war's end, the unfinished printing building was repurposed on a design by the Bank's architects Ferdinand Glaser and Rudolf Eisler. It was completed in 1925 to host the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, just weeks ahead of the introduction of the new currency, the Austrian schilling.[13]

-

1820s engraving of the Bank building on Herrengasse

-

The same building in 2006

-

The Bank complex inaugurated in 1860, pictured in 1880

-

The Bank complex, engraving after Rudolf von Alt

-

Entrance of the Bank complex on the Freyung square, 2006

-

Donaunixenbrunnen fountain placed in the Bank complex in 1861

-

Palais Hardegg on Freyung 1

-

New Nationalbank building, started as printing facilities of the Austro-Hungarian Bank, 2006

Budapest

[edit]The new Budapest head office building of the Austro-Hungarian Bank was inaugurated in 1905, and later hosted the Hungarian National Bank. It was designed by architect Ignác Alpár, with sculpture by József Róna and Károly Senyei. Its interiors were much altered after World War II; a major renovation was undertaken in 2021, with the aim to reopen the building by the National Bank's 100th anniversary in 2024.[14]

-

Budapest head office at the time of its inauguration, 1905

-

The same building in 2009

-

Allegory of the Bank, by József Róna

Branches

[edit]By 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Bank had 104 branches and 179 local offices throughout the Monarchy.[13]

-

Schebek Palace, the Bank's branch building in Prague from 1890

-

Former branch in Karlovy Vary, 2021

-

Former branch in Rzeszów, 1915

-

Former branch in Trieste, 2018

-

Former branch in Satu Mare, 1911

-

Former branch in Timișoara, 1910

-

Former branch in Pančevo, 1904

-

Former branch in Zrenjanin, 2015

-

Former branch in Sarajevo, 2012

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Jobst, Clemens; Rieder, Kilian (2023). "Supervision without regulation: Discount limits at the Austro–Hungarian Bank, 1909–13". The Economic History Review.

- Jobst, Clemens; Kernbauer, Hans (2016). The quest for stable money. Central banking in Austria, 1816-2016. Campus, Frankfurt.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Friedrich Walter (1937), "Die Wiener Stadtbank und das Staatsbankprojekt des Grafen Kaunitz aus dem Jahre 1761", Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie / Journal of Economics, 8 (4), Springer: 444–460, doi:10.1007/BF01349523, JSTOR 41793281, S2CID 155079472

- ^ a b Mira Kolar-Dimitrijević (2018), The History of Money in Croatia 1527 – 1941, Zagreb: Croatian National Bank

- ^ "1816–1818: Foundation of the bank and provisional governance". Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

- ^ a b c d e "1818–1878: The Privilegirte Oesterreichische National-Bank". Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

- ^ a b Susanne Wurm (6 February 2017). "Types of banks in the Habsburg Empire". Central European Economic and Social History.

- ^ a b c "1878–1922: The Austro-Hungarian Bank". Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

- ^ Thomas Barcsay (1991), "Banking in Hungarian Economic Development, 1867-1919" (PDF), Business and Economic History, The Business History Conference

- ^ "Governors and Presidents of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank". Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

- ^ "Oesterreichische Nationalbank". Wien Geschichte Wiki.

- ^ a b c Elisabeth Dutz (2016), "Oesterreichische Nationalbank: 200 years of architecture" (PDF), Bulletin, eabh (The European Association for Banking and Financial History e.V.)

- ^ a b "Oesterreichisch-ungarische Bank". Wien Geschichte Wiki.

- ^ "Palais Hardegg". Wien Geschichte Wiki.

- ^ a b Anna Soucek (21 November 2018). "Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Wien". Ö1.

- ^ "Main building of the Central Bank of Hungary under renovation". PestBuda.hu. 21 May 2021.

- ^ "History". Bankhotel Lviv.

- ^ "The history of the building". South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology.

- ^ "Trento" (PDF), Banca del Tempo Bolzano, p. 4

- ^ Darja Radović Mahečić (2006), Sekvenca secesije - arhitekt Lav Kalda (PDF), Zagreb: Institut za povijest umjetnosti, p. 245

- ^ "The quest for stable money, ein Buch von Clemens Jobst, Hans Kernbauer - Campus Verlag". www.campus.de. Retrieved 2023-09-24.

![Donaunixenbrunnen [de] fountain placed in the Bank complex in 1861](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/Wien_-_Donaunixenbrunnen.jpg/80px-Wien_-_Donaunixenbrunnen.jpg)

![Former branch [cs] in Karlovy Vary, 2021](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Karlovy_Vary_b%C3%BDval%C3%A1_Komer%C4%8Dn%C3%AD_banka_%2802%29.jpg/120px-Karlovy_Vary_b%C3%BDval%C3%A1_Komer%C4%8Dn%C3%AD_banka_%2802%29.jpg)

![Former branch in Lviv, 2011; redeveloped as Bankhotel[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/8%2C_Lystopadovoho_Chynu_Street%2C_Lviv_%282%29.jpg/120px-8%2C_Lystopadovoho_Chynu_Street%2C_Lviv_%282%29.jpg)

![Former branch in Bolzano,[16] 2012](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/%C3%96sterreichisch-ungarische_Bank_Bozen_-_%C3%96tzimuseum.JPG/120px-%C3%96sterreichisch-ungarische_Bank_Bozen_-_%C3%96tzimuseum.JPG)

![Former branch in Trento,[17] 2024](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Trento_Bankitalia.jpg/120px-Trento_Bankitalia.jpg)

![Former branch [it] in Trieste, 2018](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Facciata_principale_angolo_via_Geppa.jpg/120px-Facciata_principale_angolo_via_Geppa.jpg)

![Former branch in Zagreb, designed by Lav Kalda [hr], [18] 2024](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/40/Zagreb_AustroHungarianBank.jpg/120px-Zagreb_AustroHungarianBank.jpg)

![Former branch in Split (right),[2]: 160 2017](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Split-Prokuratien-2.jpg/120px-Split-Prokuratien-2.jpg)

![Former branch [sh] in Sarajevo, 2012](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/BOR_Bank_in_Sarajevo.JPG/120px-BOR_Bank_in_Sarajevo.JPG)